Kristallnacht: 81 Years Later

As 2019 marks 81 years since the horrific events of Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, the number of first-hand account from the night has ever grown fewer. Hearing the stories of survivors is more vital now more than ever.

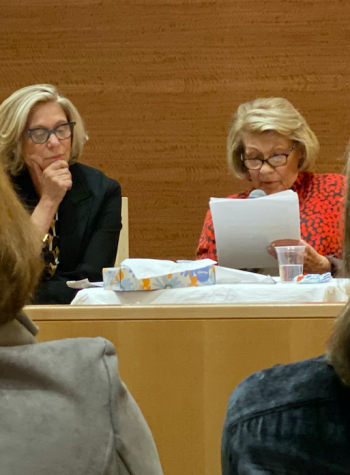

On Thursday, November 7th, Esther Peterseill, a 95-year old Holocaust survivor and KJ member, shared her story with the KJ/Ramaz community. Ms. Peterseil was born in 1924 in Bendzin, Poland, a town with a pre-war population of 50,000 people, 90% of whom were Jewish. She was born into a family of eight children.

First, Ms. Peterseil and her family were sent to a ghetto in Bendzin, living 3-4 families in a room. She said that each day, she was “fighting for a piece of bread, struggling with diseases, and waiting for the next deportation.” The Jews in Bendzin worked in sweatshops, making the uniforms for the German soldiers who were fighting on the Russian front. While she was in the ghetto, there weren’t many deportations because Birkenau was not yet complete.

In 1943, after being taken from the Bendzin ghetto and put on cattle cars for six hours, she arrived at Birkenau with a few family members, including her younger sister, her mother, and her brother. When the adults were separated from the children, Ms. Peterseil took on the responsibility of being her sister’s mom. Ms. Peterseill explained the conditions upon arrival, describing how beautiful girls’ hair was shaved and 12 girls slept on one bunk with one blanket. All inmates were given a bowl which they used for the occasional porridge or as an outhouse.

Ms. Peterseil told of the moments when she prioritized her sister who had a heart problem as a result of an untreated strep throat infection she got in the ghetto. She would give her sister her own bread rations to ensure her survival. She also told a specific story of true family love when she saved her sister from the gas chambers. During the winter, Ms. Peterseil was standing outside in the snow with no shoes (resulting in her losing toes) when a German guard walked by and commented on her superb health. At that moment, Ms. Peterseil told the guard that her sister who was on her way to be killed was healthier than herself, although she truly was not. The guard gave Ms. Peterseil the sheet and she crossed off her sister’s name, saving her life. Around that time, Ms. Peterseil’s brother, who was also in Birkenau, died.

She and her sister both survived a death march and were liberated in Germany in 1945. Ms. Peterseil says that throughout the death march, she needed to encourage her sister to continue.

Unfortunately, Ms. Peterseil’s sister died at a displaced persons (DP) camp. As she spoke of this time, Ms. Peterseil became emotional as she had the closest tie to her sister and felt like she lost a part of herself. She married her husband at a DP camp in Austria and had two children before immigrating to the United States in 1949.

An experience on the subway made Ms. Peterseil realize that people today are not educated about the Holocaust. When she was a young woman, wearing a sleeveless dress on the subway, the people next to her saw her tattooed number from Birkenau. They thought she had been imprisoned for a crime after seeing the tattoo and found it so sad that a young lady had committed a crime. Little did they know that she had survived the horrors of the Holocaust, and it was actually the Germans who had committed the crimes.

Today, Ms. Peterseil ends all of the stories she tells with a message for the youth. She remarks that, “as a Jew who has experienced the birth of the Jewish nation, a bright light of freedom, and remembrance, I felt protected again. I know in my heart that the potential for evil, the teaching of hatred, never goes away. It is up to you to see the signal. Remember what I have told you and fight, fight to make sure it never happens again.” The applause and respect demonstrated the audience’s clear support and compassion for Ms. Peterseil’s life story.

Gabby is so excited to be an Editor in Chief of The Rampage. Gabby began writing for The Rampage freshman year and has been an integral member of the paper...